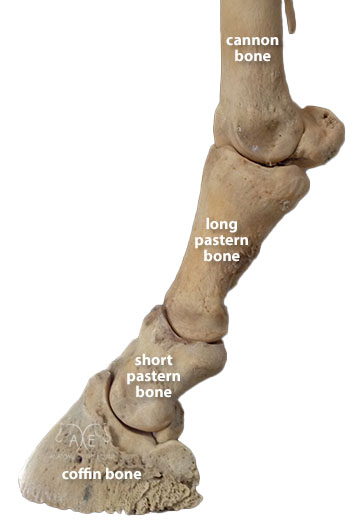

Coffin Bone - the foundation of the equine hoof

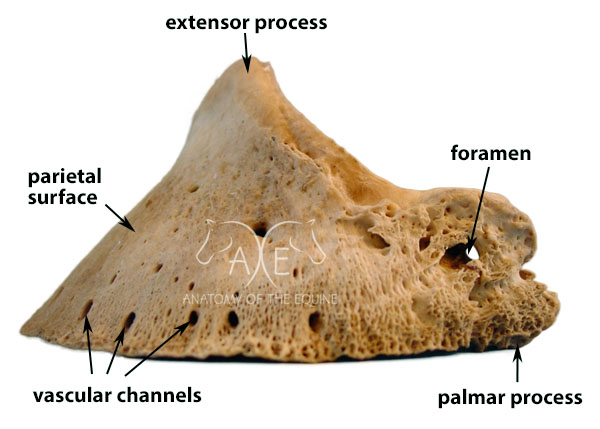

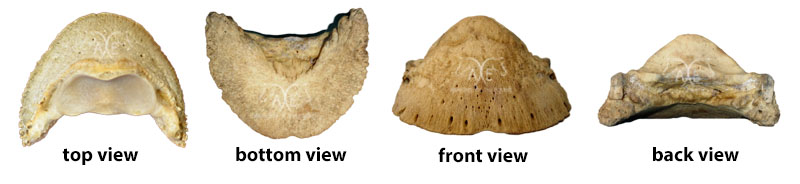

The coffin bone, also known as P3 (phalanx 3) or the pedal bone, forms the foundation of the front half of the hoof capsule, and dictates its form. It is a very unique bone as it is triangular in shape when viewed from the side, and semi-circular when viewed from the top. It is significantly lighter in weigh than the other bones in the hoof due to it being very porous which allows a vast network of blood vessels to run through it. These blood vessels help to both nourish the structures in the hoof, and absorb shock which aids in circulation by forcing blood back up the horse’s leg.

The coffin bone is surrounded on two sides by coria: the lamellar corium on the parietal (top) surface and the solar corium on the underside.

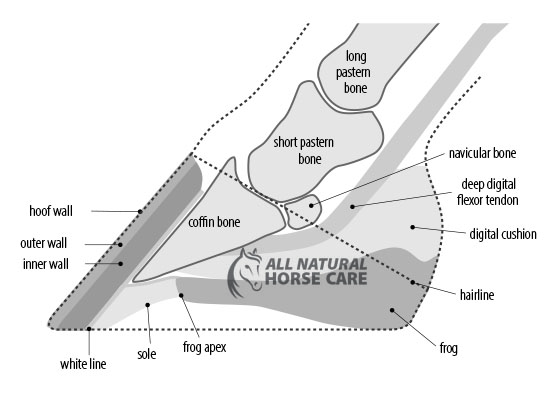

The lamellar corium serves two purposes: 1) it forms a very strong connection with the hoof wall and 2) it produces hoof wall material called intertubular horn. The coronary cushion produces a second type of wall material known as tubules, which look like tiny straws, and these grow down from the coronary band. The intertubular horn produced by the lamellar corium grows outwards and fills the spaces in between the tubules, hence its name. The combination of these two materials makes up the hoof wall. It takes on average, 9-12 months for the hoof wall to grow from the coronary band to the ground.

When a horse gets laminitis, the laminar connection becomes inflamed. Lamin (belonging to the lamina) -itis (inflammation). This is an extremely painful condition, not only because the hooves bear all the horse’s weight, but also because the hoof wall cannot swell, so the inflammation causes a huge amount of pressure within the hoof capsule.

The solar corium produces the sole material. The sole grows uniformly forwards and down from the corium and therefore the sole mimics the concavity of the coffin bone. On a healthy hoof the concavity is deepest in the collateral grooves and gently cups out right to the edge of the hoof wall. Under ideal conditions, it takes approximately 3 months to achieve full sole thickness.

In a healthy hoof, the hoof wall and sole mimic the shape of the coffin bone, producing a round shape at the front of the hoof capsule and a concave shape on the underside of the hoof. Hind coffin bones are a little more pointed at the front, and therefore produce a more shovel shaped hoof wall at the toe on hind hooves. They can also be more concave on the underside. Both these features evolved to aid in propulsion in the hind end of the horse.

Because the connection between the coffin bone and the hoof wall is so strong, the front half of the hoof capsule is very rigid. This is so that it can withstand the pressures of the horse pushing against the ground as it moves forwards.

The lateral cartilages attach to the palmar processes on either side of the coffin bone and form the structure of the rear portion of the hoof. They are more flexible than bone which allows the back of the hoof to deform to absorb shock.

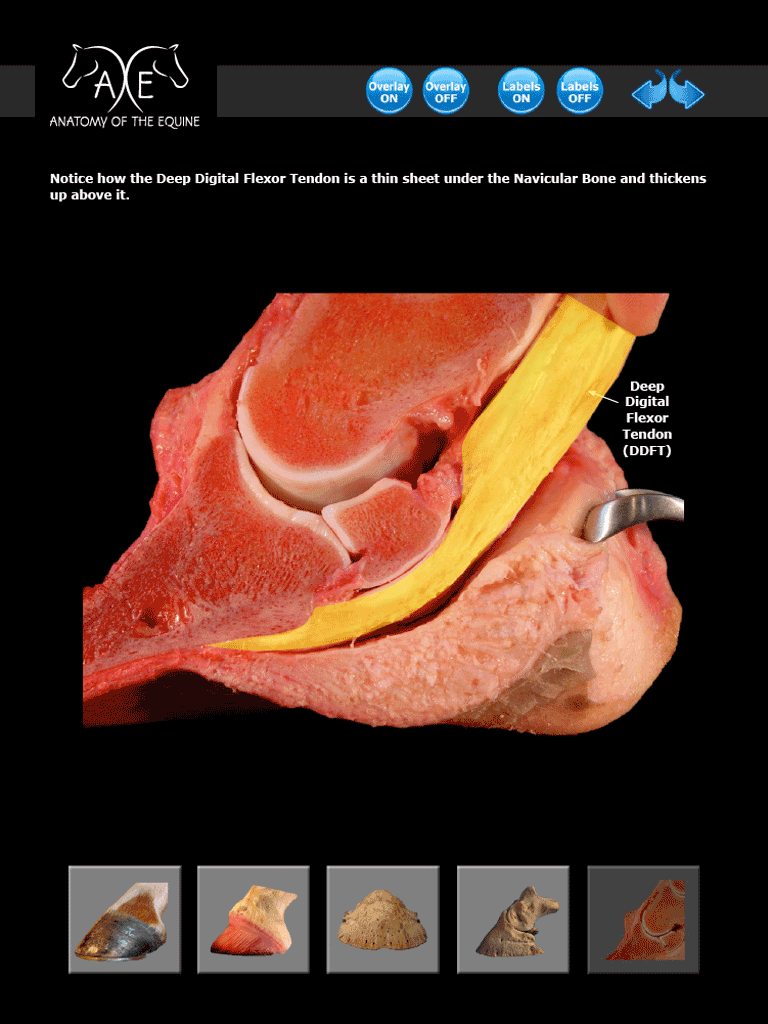

Many of the tendons and ligaments in the lower leg attach to the pedal bone. The extensor tendon attaches to the extensor process on the top of P3 and the deep digital flexor tendon passes over the navicular bone and attaches to the underside of the coffin bone.

Coffin bones vary in width and depth but there is very little difference in height. That is why the hoof of a draft horse can be wider and longer than a quarter horse but are generally not taller.

The widest part of the hoof directly corresponds to the

width of the coffin bone.

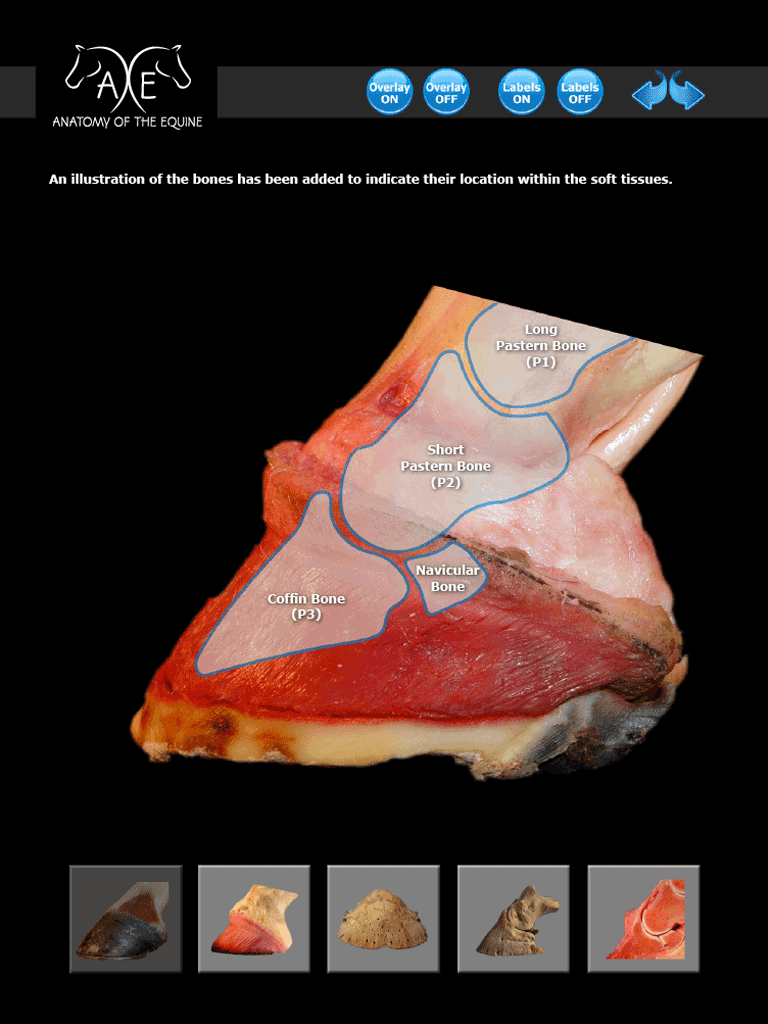

Cross section of the hoof capsule

In a healthy hoof, the pedal bone sits up high in the hoof capsule, with the top of the extensor process being in line with the junction of the hoof capsule and skin, at the front of the toe. The bottom edge of P3 sits at a 3-5° angle to the ground.

When you view a cross-section image of a hoof, the angle of bottom edge of the bone appears much steeper but that is because you are seeing the concavity in the middle of the bone, not the bottom edge. The photos below illustrate this further.

Full coffin bone on the left compared to a cross section on the right

Conditions that affect the coffin bone:

- Laminitis/Founder

- Distal descent

- Pedal osteitis

- Hoof cracks

- Keratomas

- Flares

- Fractures

Want to Learn More?

The Coffin Bone eBook

|

|

- Study the complex design of the equine hoof

- 44 stunning, high resolution, full color dissection photos and illustrations

- Easy to navigate

- Explore inside the hoof to fully understand the structures

- Clear labels

- Close-up, unique views

Available as an eBook (which works on every device)